Forgotten Heroes: A South African in Athens -- "Pat" Pattle DFC & Bar

Squadron Leader “Pat” Pattle DFC & Bar is most commonly remembered as the highest scoring “ace” of the RAF in WWII. Yet my reason for including him in this (totally subjective and highly personal) series of “Forgotten Heroes” is his service to my adopted country: Greece.

“Pat” Pattle was born 3 July 1914 in South Africa, the son of British South Africans, and named after his paternal grandfather Marmaduke Thomas. As a boy he went by “Tom.” His grandfather had been a captain in the Royal Horse Artillery before emigrating to South Africa in 1875. Pattle’s father also served in the Boar War, fought in the Natal Rebellion and again in the First World War. He served briefly in the police force before taking up farming in South West Africa. Here Tom grew up learning how to fend for himself in the desert and how to shoot very well.

Tom went to school in boarding school in Grahamstown and graduated in 1931. Although he already wanted to learn to fly, the South African Air Force turned him down because he did not already have flying experience (as other candidates did). He worked as a mechanic in a petrol station and he took a course at a commercial college that eventually led him to a clerical job and from there to a laboratory job with a gold mining company. He liked the latter work well enough to consider pursuing a degree in mining engineering, but an encounter with an aircraft — his first in the flesh — and a “flip” given by the pilot turned his head. He quit the mining company and joined the Special Service Battalion of the South African army in the hope of getting into the South African Air Force via the “back door.”

Instead, he saw an announcement in a newspaper that the RAF was offering short-service commissions to young men with a school-leaving certificate who otherwise met their criteria. Pattle immediately applied, passed the screening interview in South Africa and his uncle paid for his passage on a steamer to London to face the RAF Selection Board. Although at the time he hoped for a career in aviation, either through a permanent commission in the RAF or in civil aviation, Pattle could not know that he would never see his homeland or his family ever again.

Two weeks after his arrival, Pattle had been accepted for training and reported to the Civil Flying School at Prestwick at the end of June 1936. Here he introduced himself as “Pat” for the first time, and the name stuck with him throughout his RAF career. He proved a natural pilot, who soloed early and easily, and hen he completed training in March 1937, his flying was rated “exceptional.” Furthermore, he was conscientious about studying, something that resulted in consistently high scores on his written examinations. Meanwhile, his accurate shooting astonished his instructors.

At the end of training, he was post to No 80 (Gloucester Gladiator) Squadron and promoted to Pilot Officer on 27 July 1937. In October, he had already been appointed Squadron Adjutant, a tribute to his reputation as hard-working, serious and reliable. Less than a year later, No 80 Squadron was transferred to Egypt to defend the Suez Canal against growing Italian aggression. For Pat, this was a step closer to home, and he welcomed the move.

At the outbreak of the Second World, the squadron was moved to the Libyan border. In the lull before the real fighting began, Pat focused on improving his physical condition and trained himself to “see” better by systematically searching the sky. He also took a keen interest in the condition of his aircraft, spurring his ground crew to greater efforts, despite the very high standards already provided.

On 4 August 1940 — while the Battle of Britain was still in the early phases — Pat experienced combat for the first time. Although the squadron was slowly being equipped with Hurricanes, Pat’s flight still flew the bi-plane Gladiators. In an encounter with Italian aircraft, Pat claimed his first victory, an Italian Breda bomber, but was himself shot down when after several dog-fights he was confronted by an entire squadron of Italian Fiat CR-42s. With his guns already out-of-action from the earlier dogfighting, Pat attempted evasion, but the Italians got the better of him, shooting up his rudder. Pat took the badly damaged aircraft up to 400 feet and there jumped out over the desert.

At the time he bailed out, he was only a few miles behind enemy lines. Unfortunately, he became disoriented in the desert and walked in the wrong direction much of the night. It was noon of the following day before he crossed back into Egypt. Here he had the good fortune to be picked up by a passing column of the 11th Hussars.

This experience left a psychological mark on Pat. He became determined never to be shot down again — at least not by Italians — and not to get lost again either. He purchased a compass to carry with him in the pocket of his tunic. The experience had not, however, daunted his aggressive spirit.

On 8 August 1940 the entire squadron took the war deep into Italian air space consciously seeking battle. Divided into four sections flying at different altitudes, they lured the Italians into a fight and then efficiently executed them. A total of 15 Italian fighters were claimed for the loss of two Gladiators, and only one pilot. Less than a month later, the Italian invasion of Egypt began, and on 28 October Italy invaded Greece as well.

While the Greek army rapidly proved capable of defending the mountain passes in the northwest of the country, the Greek Air Force consisted of just 200 aircraft, all of which were obsolete, while the Italians onslaught was supported by 2,000 modern aircraft. The Greek government appealed to Great Britain for aid, and the British government responded by sending two Blenheim and one Wellington squadrons. These succeeded in completely disrupting the Italian lines of supply and communication, while the Greek — poorly equipped as they were — went on a savage counter-offensive that threw the Italians out of Greece within a week.

The conflict still raged, however, and the RAF bombers had suffered significant losses. They needed fighter protection. So, No 80 Squadron was pulled out of the desert and sent to Athens arriving 16 November 1940. They were received by the Greeks with cheers, waving flags and free drinks in the tavernas of Athens. The next day they continued to Trikkala, where the three remaining Greek pilots at the field introduced them to their new environment by leading them toward the nearest Italian base. The Greeks did not have the fuel to engage, but 80 Squadron went on the offensive and downed nine Italians. It was an encouraging start, which made them even more popular with the locals.

However, torrential rains and low cloud precluded flying in the succeeding days, and the squadron was not displeased to be transferred another airfield, this time in Yanina just 40 miles from the Albanian border. This was another grass airfield — kept short by grazing sheep — and it possessed neither hangers nor dispersal huts. The “mess” was in a hotel in the village. With frequent rain, the aerodrome was often more lake than field, while low cloud and high winds made flying difficult and dangerous.

Despite the conditions, Pat recognized

that the RAF still enjoyed conditions far superior to that of most of the

Greeks. It became his custom to visit the local hospital in the evening. His

biographer E.C.R. Baker describes the situation as follows:

Their work finished for the day, the pilots went off to visit the many Greek wounded soldiers housed in shocking conditions in the local hospital. It was so overcrowded that there was hardly room to move between the closely-packed beds. … The pilots shared their cigarette rations with the unfortunate Greeks, and brought some cheer amidst the miserable surroundings. … The tears in the eyes of these cheerful, hardy people, and their sincere cries of ‘Good luck, Inglisi,’ …. gave the pilots that little extra incentive and dash which made all the difference in any unequal battle.” [Baker, Ace of Aces. Silvertail Books, 2020, 113-114]

Soon afterwards, the squadron was relocated to Larissa, which had a better airfield. Here they flew frequent escort flights for RAF bombers during which the Gladiators were subjected to heavy flak. Such heavy flak, in fact, that by 6 December the entire squadron had to be stood down while repairs were undertaken. Despite working around the clock in appallingly cold and wet conditions, it took the ground crews a week to render the aircraft serviceable again. Yet even as No 80 squadron took an enforced break from the action, the Greek army was advancing through Albania, remorselessly pushing back the Italians. This advance was described vividly by American journalists that witnessed it as follows:

“…open carts, pulled by sturdy little mules, and driven by cheerful Greeks, protected from the driving rain and wind by a single piece of canvas, ploughing through the mire. Here and there a cart was held fast by the clinging mud, and the old men and women, and even small children, were scrambling around the hillsides searching for stones and branches to make the road passable again.” [Baker. 121-122]

On 21 December, Pat’s CO, Squadron Leader Hickey, was shot by the Italians after taking to his parachute. Members of his squadron saw him bail out, saw the Italians attack and the saw parachute catch fire. It was the second incident of this sort in just three days. Pat was de facto Acting Squadron Leader after Hickey’s death and improvised a Christmas celebration which included a Christmas tree decorated with candles — and trophies from shot-down Italian aircraft.

After ten days of leave, which he spent with friends in Cairo, Pat returned to Greece. By now the winter had really set in. When the squadron attempted to return to Yanina, the convoy with their ground crews ran into a blizzard.

“…a blinding snowstorm brought the lorries to an abrupt standstill. The airmen huddled together for warmth behind the thin canvas covering on the truck… [T]he officer in charge, Pilot Officer Patullo, immediately made arrangements to evacuate the airmen to the village of Malekas, a tiny hamlet eight miles away at the foot of the mountains. The local villagers, tough sturdy peasants, received the men with open arms, providing them with bowls of hot, steaming soup, thick black boiling coffee, and warm blankets in front of a blazing fire. Without this help, most willingly given by the cheerful, hardy people, some of the men would almost certainly have perished in the arctic conditions prevailing in the mountains.” [Baker, 142]

The squadron abandoned the attempt to relocate to the north and remained based in the Athens area. From here they continued to inflict damage on the enemy — to the extent they could in their aging Gladiators. On 8 February 1941, Pat received the DFC in recognition of his dogged determination and success in shooting down (by this point) more than 15 enemy aircraft. The official citation noted “he has been absolutely fearless and undeterred by superior numbers of enemy.” Although not noted by the official citation, Pat also showed exceptional dedication to the men serving under him, repeatedly personally carrying out searches for missing pilots, regardless of the weather.

Shortly afterwards, Pat was given the first six Hurricanes assigned to the squadron and sent to Paramythia to operate from here. On 28 February in a combined operation of 80 and 112 squadrons, 27 Italian aircraft were destroyed and eight damaged in a single engagement for the loss of a single Gladiator. Pat contributed to the total score by bringing down three Italian fighters.

On 12 March 1941, Pat was promoted to Squadron Leader and posted as CO of No 33 Squadron. Thirty-three squadron had been in the Middle East longer than 80 Squadron and was made up mostly of regular officers but from vastly different backgrounds, including a Rhodesian, Kenyan, Canadian and another South African already. They were individualists, proud of being disrespectful of authority, and Pattle told them they looked scruffy and lacked flying discipline. However, they had also all been flying Hurricanes for six months rather than only a few weeks. Pattle used this to his advantage by suggesting he needed some practice dogfighting. This gave his new command an opportunity to judge his flying abilities — and he gained their respect in a spectacular dogfight with the pilot from 33 Squadron the others had thought best capable of "defeating" him.

On 22 March, No 33 squadron went operational from the airfield in Larissa — a town no longer recognizable because it had been all but flattened by an earthquake and Italian bombing. The following day, 33 Squadron escorted Blenheims on a bombing raid. On 6 April, Germany invaded Yugoslavia and entered the conflict with Greece. The same day, on an offensive patrol over Bulgaria, Pattle encountered the Luftwaffe for the first time in his career when No 33 Squadron took on a squadron of Me 109s. The outcome: five Luftwaffe fighters shot down without losses to the RAF. In the days to follow, Pattle and his pilots continued to give far better than they took. In total, in the fourteen days following the German entry into the war, Pattle shot down between 25 and 35 enemy aircraft. (The official records have been lost precluding a definitive count.). On three separate days, he claimed five enemy aircraft shot-down, and on 19 April he claimed his largest number of victories in a single day: six.

But the situation on the ground looked completely different. Outflanked by the advancing Wehrmacht, the Allied ground forces were forced to pull back — initially to Thermopylae. All airfields north of this point, including Larissa, had to be abandoned. Only three airfields remained opened, one immediately south of Thermopylae and two in the vicinity of Athens. From these, the remaining RAF fighters tried to protect the retreating Allied troops, but their airfields came under increasingly frequent and devastating attacks from the Luftwaffe.

By 20 April 1940 the British and Allied forces were preparing a seaborne withdrawal from Greece. The Luftwaffe ordered concentrated attacks on the congested shipping in Piraeus Harbour — including dive bombing a hospital ship. To stop them, the RAF had only 15 serviceable Hurricanes left. Despite suffering from a high fever and chills, Pattle took off. He downed one Ju88 and two Me109s, but he paid with his own life. He was one of four RAF pilots killed in this engagement, known as the Battle of Piraeus.

Pat

Pattle had left South West Africa to learn to fly and ended up dying

over Athens in a conflict that only tangentially impacted his country's

fate. It would have been easy for him -- and his parents -- to feel

misused and resentful. Yet his letters and his actions suggest rather

that he identified strongly with the Greek people and fought out of a

sincere conviction that he and his men were engaged in a just struggle

-- one worth the sacrifices made.

Winston Churchill famously said when speaking of the Greek defiance of fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: “Hence we will not say that Greeks

fight like heroes, but heroes fight like Greeks.” Pat Pattle fought like a Greek. He deserves to be remembered.

(Source: Baker, E.C. R.. Ace of Aces: The Incredible Story of Pat Pattle — the Greatest Fighter Pilot of WWII. Silvertail Books, 2020.)

My novels about the RAF in WWII are intended as tributes to the men in the air and on the ground that made a victory in Europe against fascism possible.

Lack of Moral Fibre, A Stranger in the Mirror and A Rose in November can be purchased individually in ebook format, or in a collection under the title Grounded Eagles in ebook or paperback. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

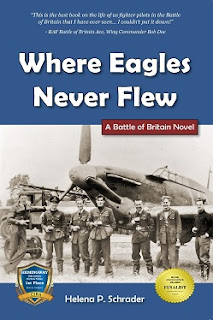

Where Eagles Never Flew was the the winner of a Hemmingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

Comments

Post a Comment